Battle, since time old, has been assumed to be the sphere of men. When the Odyssey raided Troy, Penelope stayed in Ithaca to stay. And when women want to go to war, they will be depicted with manly carbons from argumentative Amazons to the facade Mulan. Women are the weaker coitus. They need to be defended, so they're put in the reverse. War stories are substantially told from men's perspectives and by men Homer, Tolstoy, Hemingway, Remarque, Sebastian Faulks, Graham Greene, and so on. Who wants to hear a woman tell a war story? After all the epic, painful, or dazing effects that so numerous men have created, What more do women have to say about war?

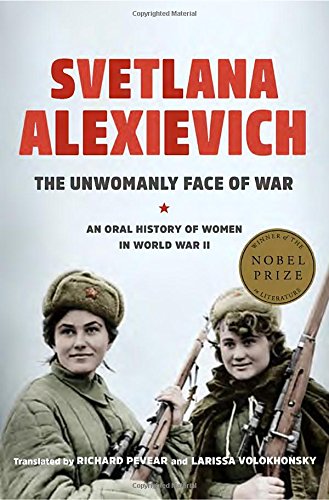

War Without a Woman's Face is a work that presses deeply into the boundaries of boundaries. Women, women, women. Svetlana Alexievich has pulled these women out of the murk of the decades since the end of the World War, where they have been hiding or forgotten, where they have tried but noway forgotten the war that took their lives. They aren't only youthful times. With her heart, vision, and archivist, Svetlana Alexievich has collected every piece of memory and woven them into a masterpiece enough to move people.

When Svetlana Alexievich was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2015, public opinion aroused a certain surge of excitement. Svetlana Alexievich isn't a pen; she's real intelligence, and her workshop is the immediacy of erudite literalism and journalistic reportage. War without a woman's face is considered a typical work for this mode of composition. Over time, Alexievich canvassed hundreds of women who fought in World War II under the Soviet flag and also sifted and organized them into a unified total, portraying a war like no other. That was formerly discovered war is filled with women's faces.

In the first part of the book, Svetlana Alexievich writes:

Had to write a book about war so that the reader would become deeply nauseous of it, showing them that the mere idea of war was infamous. Mental.

She made it. War without a woman's face is indeed enough to make compendiums have some silly moments. A nanny was killed, her eyes cut off her bone and piled it, a youthful boy was sawed in half, a military croaker in an exposed front had no tools and was forced to use her teeth to tear the damaged meat of wounded dogfaces to save him, or scenes depicting butchery, depicting blood, depicting mortal meat as white as funk, obviously all can make the anthology squeamish. But no, people are presumably most revolted when they see those womanish stagers relating these effects when they've been down from the war for decades. They talked as they cried, breaking sometimes to ease the palpitating pain in their hearts. They expose the cracks in their souls the moment someone eventually listens to them. There's no more war and peace, only war and palm. Palm doesn't mean peace. Because war, it turns out, has no way ends.

This work is a wordbook of war, indeed though it's recited nearly simply by women. From gunners, womanish nonmilitary commanders, tank crewmen, and anti-aircraft gunners to mechanics, croakers, nurses, cookers, launderers, etc., everyone has their own story to tell. about the same war. Hundreds of people but not a single story is duplicated. To emphasize gender identity, Svetlana Alexievich also arranges the narratives according to a woman's life cycle when they're little girls, also women with love, women and, eventually maters. The war hit every stage in the lives of Soviet women. It's always visible, it may be destructive, it may not be, but after going through the war, no bone is the same as it used to be. Like after a military reclamation, they walked in with lacings, long dresses, and thrills, but also walked out with shaggy men's haircuts, jackets, and thrills that were five bases bigger than their bases. No women, only dogfaces.

When women go to war, they not only give their youth, health, life, and family like any man, harsher, but they also immolate their womanish divinity. Because like I said, there's no place for women on the battleground. No separate uniforms, no separate musts, no separate governance. It's a man's world and if women are to enter, they've to follow the same laws as men. therefore, in the great war with the Germans, Soviet womanish dogfaces also had to fight in a lower but inversely fierce battle fighting their own womanish characters. Some women fully excluded it during their military service, they indeed stopped menstruating. Others cover their warm hearts with womanish continuity they find ways to maintain their embroidery conditioning, hide a flower scarf, put on a beautiful chapeau, ready to sleep to sit down to sleep. wearing that chapeau a little longer Are those effects frivolous? Yes, if for men, no, if they're women.

Women are delicate and emotional, they're born to love, to give life. thus, war from the perspective of women also has fully different angles. The women themselves go to the battleground, but they go after the men. Women not only see the war, the brutal adversary, and the motherland in peril, but they also see the whole world that embraces all of this. They saw cranes flying across the sky, saw cherry blossoms bloom in spring, saw the man they loved fall, and saw empty German children on the other side of the line. Women, they always carry the look of a Mother. Svetlana Alexievich's substantiations always feel to see everything through the lens of compassion. Because of love, they go to war, fight, die or survive, detest and forgive.

"War" then's no longer a conception, much less content or an environment. In Svetlana Alexievich's book, war has come a living reality with thousands of faces replayed through numerous recollections that have noway been duplicated. Each history adds a brushstroke to the face of war. War is the main character throughout the entire book. fractured and unified, collectively and inclusively, Alexievich transforms his work into a world that's constantly on the move, always reverberating with voices, rolling over mortal lives.

And so, although War Without a Woman's Face is a pictorial account of World War II reaching far down in Europe decades ago, the first thing that came to my mind when I read it was that stagers our legionnaire- read this book. What will they feel to relive in their hearts before such an analogous war portrayal? Because indeed for someone who sounded to have been so far down from the last war of his nation, he now realizes that he's actually too close. Ever, I still understand. perhaps it's because I am still in the same" generation" as Alexievich the children of parents who went to war.