I've known the plot of Mary Shelley's extremely popular, classic work since reading its abbreviated form in the Oxford Bookworms series. As a result, I had a rudimentary understanding of the fundamental premise of "Frankenstein," a novel that practically everyone has heard or read about, about scientific student Victor Frankenstein who experimented and developed a living entity by grafting dead people's parts and sending electricity through them. Then, appalled by the horrific form of his creation, Frankenstein rejected it, abandoning it to roam in search of refuge. Faced with the expulsion, beating, and isolation of humanity, the creature returned to exact revenge on Frankenstein by killing his loved ones. Then it all becomes a lengthy sequence of vengeance, beginning at the North Pole, where Frankenstein chases the creature but is always sluggish, and finishing at the North Pole, where Frankenstein died without doing it. fulfill your desire

That's about it, and of course, Mary Shelley's obvious message in her book, which she penned when she was just 19 years old, is an effective caution to detractors. When faced with actions and innovations that might lead to calamity in the future, science can help. Even the work's subtitle, "A Modern Prometheus," emphasizes that lesson, invoking the narrative of Prometheus, the Greek mythological character who stole fire for mankind only to be destroyed. As part of the basis for the myth of Frankenstein, the gods of Olympus chastise. You should not do anything just because you are capable of doing it. Victor Frankenstein made the fateful mistake in his first step into scientific exploration, only to learn Prometheus' lesson too late, resulting in so many tragedies.

But that's not all "Frankenstein" demonstrates. Because, after thoroughly experiencing the original narrative in the original language in which Mary Shelley penned the story, I discovered that this work covers a wide range of other issues. The first issue that sprang to me was if fate influences people's decisions in life. When recalling his terrible narrative with the creature he made in the initial chapters of the work, Victor Frankenstein states that fate has played a significant role in getting him to the condition he is in today.

Fate has created a Frankenstein with an odd interest in life and how to resurrect the dead. Fate prompts Frankenstein to investigate the works of other experts, even some whose scientific beliefs have been declared antiquated and erroneous. Fate continued to propel Frankenstein to the university lecture hall in Ingolstadt, where he discovered new scientific frontiers while "cultivating" his desire to experiment to create life.

But, at any moment along the process that led to Frankenstein's creation of that malformed entity, was it truly fate? Is Frankenstein capable of interfering with the course of events and so halting what has occurred? Was Frankenstein's choice to create the creature an impetuous, frantic moment of a person enthusiastic about scientific inquiry, or was it a decision he might have made more clearly? And, in the end, do we select our own lives, or does fate choose for us? The issue of fate and human free will is always an interesting topic to discuss and investigate, especially when presented in the context of Frankenstein's narrative.

The next subject I perceive in this work is life and death, as well as the significance of birth. Mary Shelley has seen both life and death many times throughout her life. The death of her mother haunts her (and in the story, Victor Frankenstein goes through the same loss). Following that, she had a string of pregnancies and miscarriages, or her infants died at birth. Life, according to Mary Shelley, is a sign of creation, yet it is also destructive. The creature Frankenstein made reflects his inventiveness and power to create life, but it is also the agent of death.

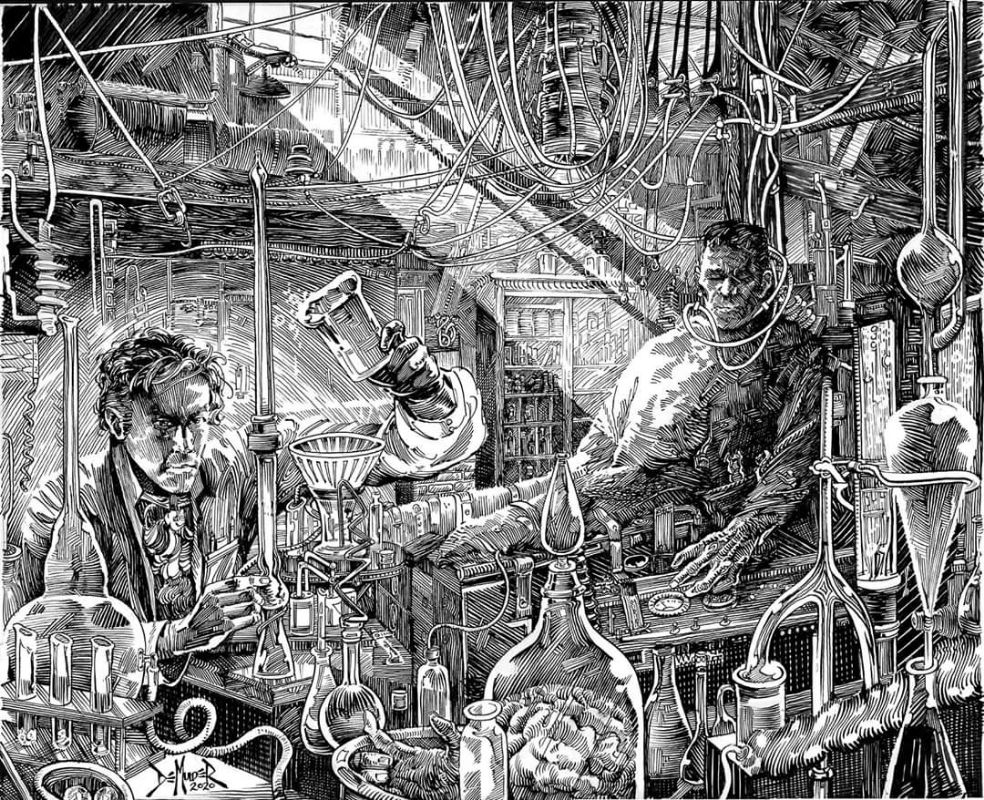

From there, we go on to the following topic: has Frankenstein's creature always been a death agent? Instead of focusing on portraying the horror in the creature's look, walk, or appearance, Mary Shelley merely devoted a few words to this. And, aside from the golden eyes that seem to see through Frankenstein's heart, and the frequently repeated word to generalize the ugliness and horror that the creature can evoke when humans see it, there aren't many details that clearly depict the appearance of the creature in the way that the image of the deformed creature created by Frankenstein is built. Perhaps Mary Shelley did not plan to write a horror story when she created this work, even though it was inspired by a wager on who could write the scariest narrative. Mary Shelley humanizes her narrative even more by having the monster Frankenstein made relate to the account of what occurred after Frankenstein abandoned it.

That creature looks to be an entity with its own thoughts, feelings, observations, imitations, language learning abilities, and the ability to observe the emotions that humans convey to the outer world. If it hadn't been for the deformed look caused by the grafted organs of the deceased, the creature could have been an excellent friend, a comrade, in the way it grasped and reasoned for itself. It found the fundamental features in the impoverished family's existence that it had discreetly watched, and subsequently longed for nothing more than to be friends with humans. Above all, that being, like every other creature born (or made) on this planet, wishes to be understood, respected, well-treated and loved. That desire transforms the horrific creature, constantly referred to as "daemon," "wretch," or "monster" by Frankenstein's words, into the most "human" figure in the text.

And who is the actual "monster" when compared to the villagers who immediately beat and chased the creature, when compared to Frankenstein himself - who made it? Episodes in which the creature describes how it was pursued and rejected when all it wanted was to connect with humans and be loved for its covert acts of kindness. I just feel endless grief because I produced humanity. If the creature was a cold-blooded "monster," as Frankenstein described it, Mary Shelley could not have poured a huge amount of empathy and genuine passion into it with her pen. who comes in like way just to be viciously rejected... That monster, like Chi Pheo's "who gave me honesty?" turned around to despise mankind and especially the one who gave it life - Frankenstein, after being rejected by the one who made it, then being rejected and kicked out by the same people it assisted. That hate manifested itself in deeds of vengeance, all of which resulted in the lives of innocent people and left Frankenstein in excruciating pain. Then, as the hate grew, Frankenstein set out to hunt the creature, both to eliminate the implications for mankind and to avenge what the creature had done to him. The second half of the tale is packed with the strong emotions of the two major characters, particularly the creature's awful suppression of wanting a mate produced in the same fashion, but Frankenstein refused to follow suit.

The "hero" and "villain" themes ("hero" and "villain") are inapplicable in this work since both main characters have good and terrible acts. Frankenstein has gone from making a mistake, creating a monster with such power but not being accountable for it, to now having the opportunity to end a vengeful entity's murdering rampage. It will leave mankind alone as long as you make it a consort, a life mate like it. However, after learning from his catastrophic error, Frankenstein was unable to construct another organism of the same strength, protecting mankind from another possible peril. But it was that choice that fueled the creature's anger. It transformed from a person full of compassion and goodwill for humanity into a murdering machine driven by the two words of revenge that constantly burned in its yellow eyes.

After all, who is to blame, and who bears the brunt of the responsibility in this tragedy? Is it Frankenstein's fault for being stupid and irresponsible? Were the people chasing the monster and murdering the beneficent portion of it in the process? Or is it the beast itself, looking for methods to exact revenge? Or are all of the personalities engaged in the disaster, complicit in the atrocities committed, their hands tainted with the blood of innocent people? "Frankenstein" highlights challenging concerns; the moral categories and the borders between good and evil are so delicate that we don't know how to respond if we placed them in that circumstance. Perhaps this is the work's most appealing feature, making it a masterpiece of international literature.

The finale is both liberating and heartbreaking. Frankenstein died without reaching his target; he died with a resentment that was continuously piling up, but his death also released him from the misery he had endured as a result of the creature he had made. And that creature will undoubtedly live forever with unending guilt for bringing its owner to the brink of death. How can this atrocity be forgotten? The narrative has ended, but the sensation it has left behind is still palpable...

/GettyImages-3172251-5c2a6c47c9e77c00015ec3c8.jpg)